Dr. Kumar’s Take:

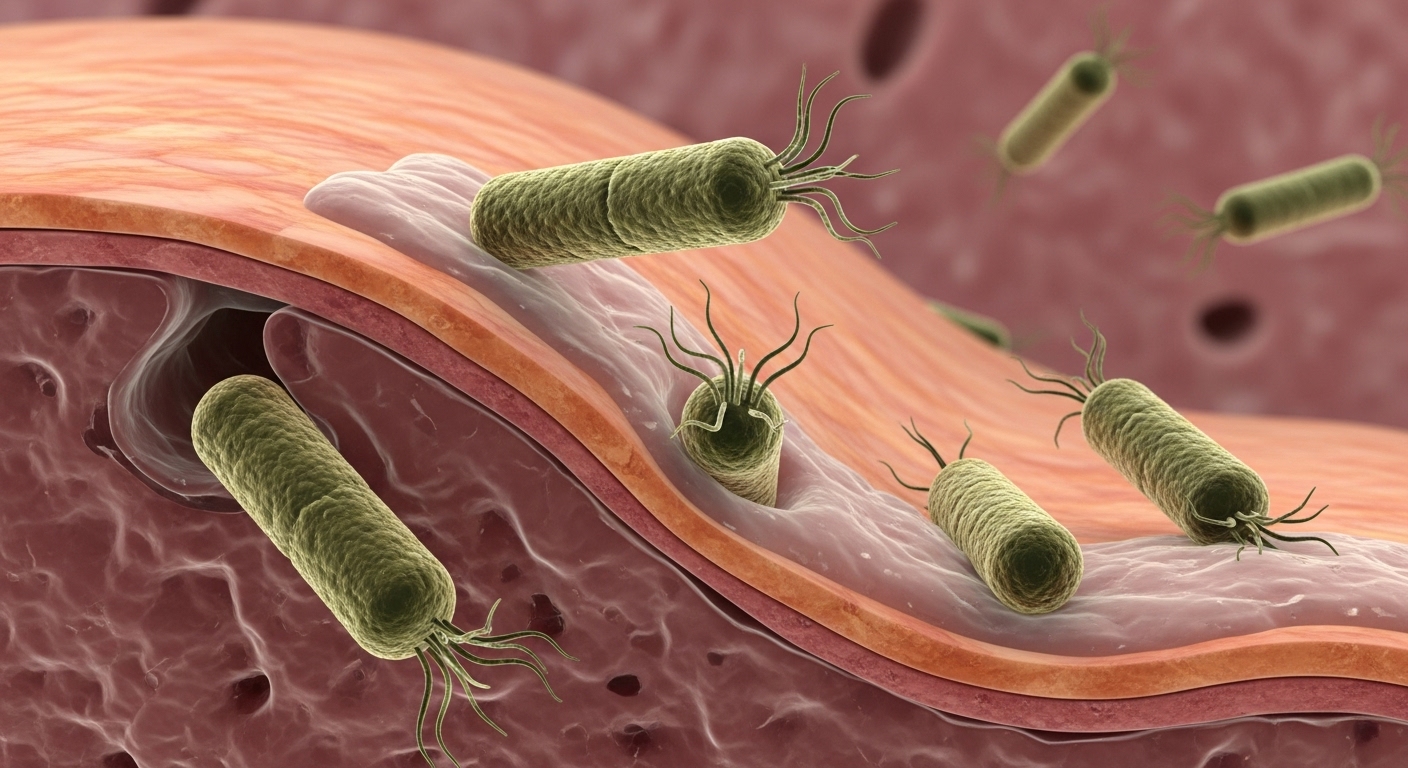

Helicobacter pylori may be the most infamous bacteria in medicine. Barry Marshall and Robin Warren discovered that this spiral-shaped bug was behind most stomach ulcers, a finding so radical it won them the Nobel Prize. What makes it fascinating is that while H. pylori can cause ulcers and cancer, new evidence suggests it might also protect against conditions like reflux disease and esophageal cancer. The real story is not about “good” or “bad,” but how this microbe interacts with our diet, environment, and genetics.

Key Takeaways:

✔ H. pylori causes more than 90% of duodenal ulcers and up to 80% of gastric ulcers.

✔ Marshall famously infected himself with H. pylori to prove it causes gastritis.

✔ Some studies suggest H. pylori may protect against reflux, Barrett’s esophagus, and esophageal cancer.

✔ Risk varies by population: Japanese have high stomach cancer rates, while Indians with high infection rates rarely develop it.

Actionable Tip:

If you are diagnosed with H. pylori, talk to your doctor about treatment, but also ask about your personal risk factors such as family history, diet, and regional cancer rates. Medicine is moving toward a more tailored approach rather than a one-size-fits-all model.

Brief Summary:

This editorial reflects on 23 years of research since the discovery of H. pylori. Once thought to be harmless, it is now recognized as the leading cause of peptic ulcers and a major risk for gastric cancer. Yet, research also shows that carrying H. pylori may lower the risk of reflux-related disorders. The paper urges ongoing study into how this microbe, our bodies, and our environment interact to shape health outcomes.

Study Design:

This was an editorial review written in 2005. It summarizes decades of evidence on H. pylori, including Marshall’s self-experiment, the genomic sequencing of the bacterium, and population studies that show both harmful and potentially protective effects

Results:

- Confirmed: H. pylori is the main cause of ulcers and a risk factor for stomach cancer.

- Controversial: Some studies show it protects against reflux and esophageal cancer.

- Population effect: Disease risk is higher in Japan but low in India despite high infection rates, suggesting environment and diet matter.

- Open question: Should medicine always aim to eliminate H. pylori, or are there cases where its presence is protective?

How H. pylori Affects the Stomach and Beyond

H. pylori burrows into the stomach lining and produces enzymes that weaken its defenses, leading to chronic inflammation. Over time this can cause ulcers or cancer. Yet the bacterium also reduces stomach acid in some people, which may protect against reflux disease and its complications. This paradox keeps researchers debating whether complete eradication is always the best strategy

Related Studies and Research

Podcast: Stomach Full of Courage – H. pylori and Ulcers – How two outsiders revolutionized medicine by proving ulcers were caused by bacteria.

Barry Marshall’s Nobel Lecture – A deep dive into Marshall’s Nobel Prize speech and the road to scientific validation.

Peptic Ulcer Disease: Clinical Overview – A clinical summary of ulcer symptoms, causes, and treatment.

Frequently Asked Questions

How common is H. pylori?

It infects about half the world’s population. Rates are falling in developed countries but remain high in developing regions.

Does everyone with H. pylori get ulcers?

No. Most people never develop symptoms. Only a fraction develop ulcers or cancer.

Could H. pylori actually be helpful?

Some evidence suggests it protects against reflux and esophageal cancer, but the risks of stomach cancer generally outweigh these benefits.

Should H. pylori always be treated?

Not always. Treatment is essential for ulcers or cancer risk, but public health experts are still debating whether all carriers should be treated.

Conclusion

The story of H. pylori is one of medicine’s greatest revolutions. It toppled the dogma that stress causes ulcers, revealed a bacterial culprit, and earned a Nobel Prize. Yet the full picture is complex. While H. pylori can cause devastating disease, it may also offer protection in certain contexts.

The challenge for modern medicine is to balance eradication with recognition of its potential protective roles, tailoring care to each patient.