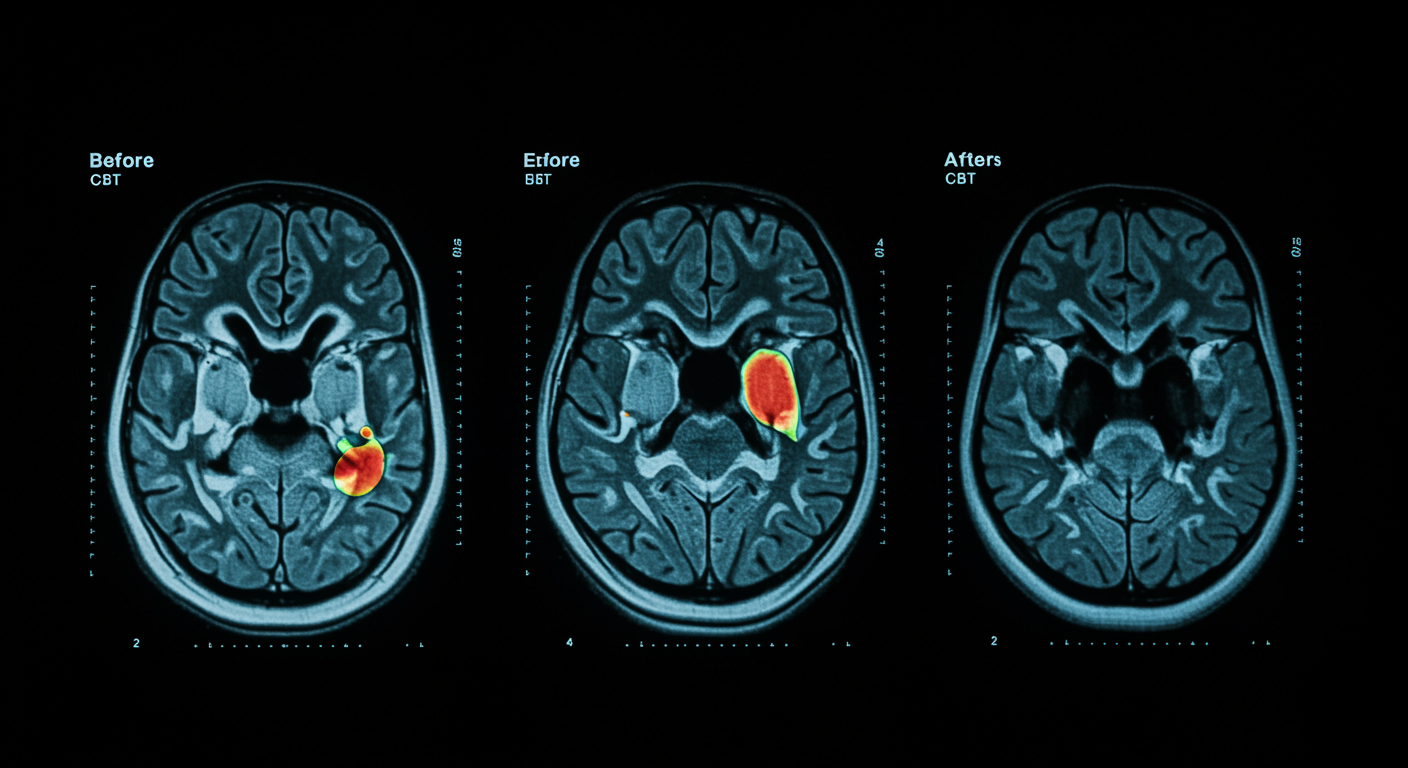

How does CBT change the depressed brain?

Yes. Cognitive behavioral therapy measurably changes brain activity in limbic, striatal, cingulate, and frontal areas, partially normalizing neural patterns associated with depression and reducing negative cognitive biases. A systematic review of 14 task-based fMRI studies published in the Journal of Affective Disorders shows that CBT produces objective, measurable neurobiological changes that correlate with symptom improvement.

What the data show:

- Limbic system changes: Six out of seven studies found significant alterations in amygdala and hippocampus activity, primarily showing reduced reactivity after CBT

- Striatal activity: Four out of five studies reported increased activity in reward processing and decreased activity during affective processing and future thinking

- Cingulate cortex: Six out of nine studies demonstrated altered activity in anterior and posterior cingulate regions, with subgenual anterior cingulate cortex changes most consistently linked to symptom improvement

- Prefrontal cortex: Seven out of eight studies found significant activity changes in frontal areas involved in emotion regulation and cognitive control

- Symptom correlation: Brain activity changes in the subgenual anterior cingulate cortex and prefrontal areas show associations with clinical symptom improvement

- Normalization pattern: CBT appears to reduce limbic hyperactivity while modulating striatal, cingulate, and prefrontal activity to restore more balanced neural processing

- Mechanism: CBT works by reducing bottom-up limbic hyperactivity (particularly in amygdala and hippocampus), increasing top-down cognitive control from prefrontal regions, enhancing striatal reward responsiveness, and normalizing cingulate activity involved in emotion regulation - these changes collectively reduce negative cognitive biases and restore more adaptive neural processing patterns that support recovery from depression

Dr. Kumar’s Take

This systematic review provides the neurobiological proof that CBT isn’t just “talk therapy” - it’s literally rewiring the brain. The fact that we can see measurable changes in limbic, striatal, cingulate, and frontal areas on fMRI scans is remarkable. These are exactly the brain regions we know are dysfunctional in depression. The limbic system processes emotions, the striatum is involved in motivation and reward, the cingulate cortex handles attention and emotion regulation, and the frontal areas manage executive function and decision-making. CBT is essentially teaching the brain new ways to process information and emotions, and we can now see this happening in real-time through brain imaging.

Study Snapshot

This systematic review analyzed longitudinal fMRI studies examining brain activity changes in depressive patients undergoing cognitive behavioral therapy. The researchers focused on task-based fMRI studies that measured brain function before and after CBT treatment, allowing them to identify specific neural changes associated with therapeutic improvement. The review examined changes across multiple brain regions and their relationship to symptom remission.

Results in Real Numbers

This systematic review analyzed 2,149 research results, ultimately identifying 14 studies that met strict inclusion criteria for examining brain activity changes during CBT for depression. Among these, 12 studies examined longitudinal changes in brain activity, while 7 studies investigated the relationship between neural changes and symptom improvement. Treatment durations across studies ranged from 5 to 49 weeks, with most interventions lasting between 10 and 16 weeks.

Limbic System Changes:

Six out of seven studies (86%) that investigated limbic areas found significant alterations in amygdala and hippocampus activity following CBT. Most studies reported decreased activity in these regions during affective processing, reward tasks, and dysfunctional attitude processing. One study found a strong negative correlation (r = -0.60, p = 0.001) between amygdala activity reduction and symptom improvement, meaning patients with greater amygdala activity decreases showed greater clinical improvement.

Cingulate Cortex Modifications:

Six out of nine studies (67%) demonstrated significant changes in cingulate regions, with the subgenual anterior cingulate cortex (sgACC) showing the most consistent associations with symptom improvement. In one study, greater increases in sgACC activity during reward processing were linked to reduced anhedonia scores. Another study found correlations of r = 0.57 (p = 0.01) and r = 0.54 (p = 0.02) between sgACC activity changes and improvements in depression scores, indicating that neural changes in this region predict clinical recovery.

Prefrontal Cortex Alterations:

Seven out of eight studies (88%) found significant activity changes in prefrontal regions. One study revealed a correlation of r = -0.44 (p = 0.034) between medial prefrontal cortex activity reduction and symptom improvement, suggesting that decreased activity in this region (potentially reflecting reduced rumination) was associated with better outcomes. Another study found a strong positive correlation of r = 0.74 (p = 0.004) between activity changes in the left precentral gyrus and depression score improvements.

Striatal Reward Processing:

Four out of five studies (80%) reported significant effects in striatal structures. Studies consistently showed increased activity in the nucleus accumbens and striatum during reward processing tasks after CBT, with one study demonstrating that greater increases in nucleus accumbens activity were associated with reduced anhedonia. This suggests CBT enhances the brain’s responsiveness to rewarding stimuli.

Treatment Response Rates:

Across the included studies, treatment response rates (defined as at least 50% reduction in depression severity) varied but were generally positive: 75% (9 out of 12 patients) in one study, 81% (13 out of 16 patients) in another, 61% (14 out of 23 patients) in a third study, and 72% (18 out of 25 patients) in a fourth study. These response rates align with typical CBT outcomes and demonstrate that the brain changes observed are occurring in patients who are clinically improving.

Self-Referential Processing:

One study examining self-referential processing found that changes in ventral anterior cingulate cortex activity during negative self-referential conditions showed a correlation of r = 0.49 (p < 0.05), accounting for 24% of the variance (r² = 0.24) in rumination improvement. This suggests that CBT’s effects on how the brain processes self-referential negative thoughts are directly linked to reductions in rumination.

Overall Pattern:

The review revealed that CBT produces a consistent pattern of brain changes: reduced limbic reactivity (particularly in amygdala and hippocampus), increased striatal reward responsiveness, and altered activity in cingulate and prefrontal regions. These changes were most consistently associated with symptom improvement in the subgenual anterior cingulate cortex, where multiple studies found significant correlations between neural activity changes and clinical recovery. The findings suggest that CBT works by normalizing the neural patterns underlying negative cognitive biases, with measurable brain changes that correlate with therapeutic success.

Who Benefits Most

Patients with depression who show abnormal activity patterns in limbic, striatal, cingulate, and frontal brain regions may benefit most from CBT’s neural normalizing effects. The review suggests that individuals with prominent negative cognitive biases may be particularly responsive to CBT’s brain-changing mechanisms.

People seeking evidence-based therapy with measurable neurobiological effects may find CBT particularly appealing, given the objective brain changes demonstrated through fMRI imaging. Patients interested in understanding how their therapy is working at a biological level may benefit from knowing about these neural mechanisms.

Safety, Limits, and Caveats

While CBT produces measurable brain changes, the review notes that these changes are only partially associated with symptom remission, indicating that neural normalization may be incomplete or that other factors also contribute to recovery. Individual responses to CBT vary, and not all patients will show the same patterns of brain changes.

The studies reviewed were limited by sample sizes and methodological variations, and longer-term follow-up is needed to understand the durability of CBT-induced brain changes. The relationship between brain changes and clinical outcomes requires further investigation.

Practical Takeaways

- Understand that CBT produces measurable, objective changes in brain function that can be seen on fMRI scans

- Recognize that CBT works by normalizing abnormal brain activity patterns in key regions involved in emotion and cognition

- Consider that the brain changes from CBT may take time to develop and may continue evolving throughout treatment

- Prepare for the possibility that neural changes may precede or follow clinical improvements, with individual variation in timing

- Stay engaged with CBT knowing that it’s creating real, measurable changes in your brain’s functioning

What This Means for Depression Treatment

This systematic review provides neurobiological validation for CBT as an evidence-based treatment that produces measurable brain changes. The findings support CBT’s effectiveness by demonstrating that it literally rewires dysfunctional neural circuits associated with depression.

The research also suggests that brain imaging could potentially be used to monitor treatment progress and predict which patients are most likely to benefit from CBT based on their neural response patterns.

Related Studies and Research

Episode 31: Depression Explained — The Biology Behind the Darkness

Episode 32: Depression Recovery Roadmap: A Step-by-Step, Evidence-Based Plan

Different CBT Components Affect Specific Cognitive Mechanisms

FAQs

How long does it take for CBT to change the brain?

The review examined longitudinal changes, but specific timelines vary. Brain changes may begin within weeks of starting CBT and continue evolving throughout treatment.

Are CBT brain changes permanent?

While the studies show measurable changes during treatment, longer-term follow-up research is needed to determine the durability of CBT-induced neural modifications.

Can brain scans predict who will respond to CBT?

The research suggests this possibility, but more studies are needed to develop reliable predictive biomarkers based on brain imaging patterns.

Bottom Line

Cognitive behavioral therapy produces measurable changes in brain activity across limbic, striatal, cingulate, and frontal regions, partially normalizing neural patterns in depressed patients. These objective brain changes provide neurobiological evidence for CBT’s effectiveness and help explain how “talk therapy” creates lasting improvements in depression.