What If We’re Destroying the Cure?

I watched Avatar: Fire and Ash last week, and I couldn’t shake a simple, unsettling thought. What if the most valuable thing on that planet wasn’t the glowing forests or the spectacle, but something small, biological, and easily destroyed before anyone understood what it could do?

That idea followed me into work the next day. Because in medicine, that’s not science fiction. That’s history. Some of the most important therapies we’ve ever used came from nature, discovered by accident, adapted to be used for the betterment of mankind. And plenty more were almost certainly lost before we ever knew they existed.

The Mold That Changed Medicine

One of those discoveries began with something no one was supposed to notice.

In 1928, a microbiologist named Alexander Fleming returned to his lab and found that a petri dish had been contaminated by mold. In most labs, that dish would have been thrown away without a second thought. Instead, Fleming paused. Around the mold was a clear ring where bacteria couldn’t grow. Something small and biological was killing something dangerous, quietly and effortlessly. That mold turned out to be Penicillium, and the substance it produced became penicillin.

What makes that moment remarkable isn’t just what was discovered. It’s how easily it could have been missed. Penicillin wasn’t engineered. It wasn’t designed. It was noticed. And even after Fleming published his observation, the discovery nearly stalled out entirely. It took years, a world war, and an extraordinary effort by scientists, clinicians, and manufacturers to turn that fragile substance into a real drug that could save lives at scale.

That story, from a contaminated dish to a battlefield-saving medicine, is the focus of my latest Tribulations episode. It’s a reminder that some of the most powerful advances in medicine come from patience, attention, and respect for the natural world. If you want to hear the full story of how penicillin was discovered, and how it went on to change the course of medicine and World War II, you can listen here:

Apple Podcasts | Spotify | My website

When Biology Pushes Back

Penicillin worked almost too well.

Once antibiotics entered routine medicine, infections that had once been terrifying became expected to respond. And over time, that expectation quietly turned into overuse. Bacteria, of course, did what bacteria always do. They adapted.

What started as an early warning in the 1940s is now a daily reality in hospitals. In the United States alone, antibiotic-resistant infections cause tens of thousands of deaths every year, and globally the number is far higher. These aren’t rare or exotic cases. They’re ordinary infections that no longer behave the way we expect them to.

I broke down the real scope of this problem, with concrete numbers and examples, in a separate review here:

2019 Antibiotic Resistance Threats Report

And this is the uncomfortable tension. One of the greatest gifts nature ever gave us is starting to fail. Which forces a bigger question. When our miracle tools stop working, where do we look next?

Using Biology to Fight Biology: Meet the Bacteriophage

So medicine is being pushed back toward an older idea, one that predates antibiotics altogether.

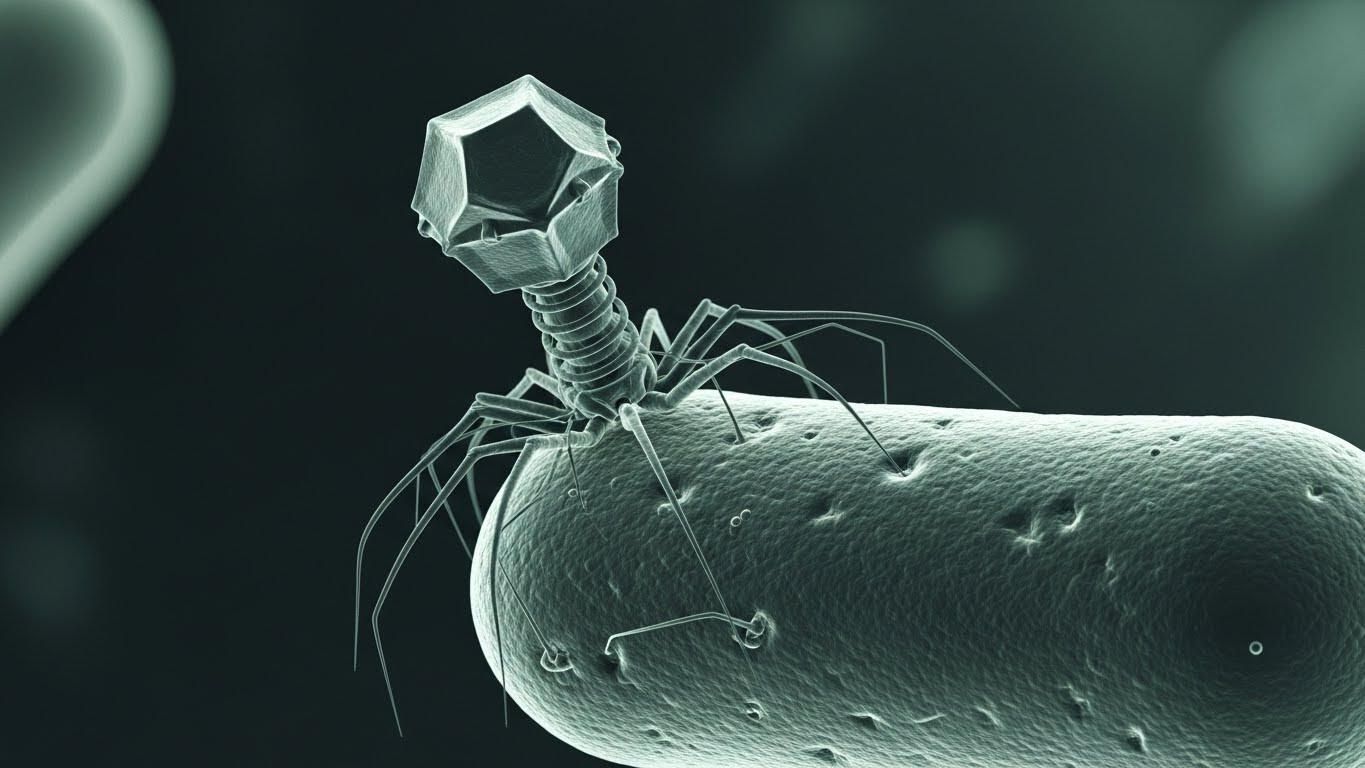

Long before penicillin, physicians were experimenting with bacteriophages. Viruses that infect bacteria and only bacteria. They attach to a specific bacterial cell, inject their genetic material, replicate, and destroy it from the inside. It’s targeted, biological, and elegant. But phage therapy was messy. Matching the right phage to the right bacterium was slow and imprecise, and antibiotics were simply easier. So phages were shelved.

Now they’re back, not because they’re trendy, but because necessity is forcing us to rethink our tools.

What’s changed isn’t the biology. It’s the technology. We can now rapidly identify bacterial strains, sequence them, and match them to specific phages. In real clinical settings, phage therapy is being used through compassionate-use programs for patients with multidrug-resistant infections that no longer respond to antibiotics. Sometimes phages are used alone. Sometimes they’re paired with antibiotics to regain control of infections that had already slipped past our defenses.

I walk through how this actually works in practice, including the limitations and where the promise really lies, in this mini-review:

Mini-review: Insight of Bacteriophage Therapy in Clinical Practice

When our clean, scalable solutions fail, medicine doesn’t invent something entirely new. It turns back to biology. To systems that evolved over millions of years. To solutions that were always there, waiting for us to catch up.

The Treasures We Never Find

What struck me most about Avatar : Fire and Ash wasn’t the scale or the visuals. It was the idea of Pandora itself. An impossibly rich, interconnected biome, full of biological life with layers of value no one fully understands. The Na’vi live within it, protect it, and treat it as something sacred. The humans arrive with a very different mindset. Extract what’s obvious. Take what’s valuable now. Worry about the consequences later.

That story isn’t subtle, but it’s effective. Because we’re doing the same thing here.

On Earth, our oceans, rainforests, and ecosystems are biological treasure troves. They’re not just beautiful. They’re chemically rich. Evolution has spent billions of years experimenting, refining, and optimizing molecules that interact with living systems. And medicine has been quietly borrowing from that work for decades.

The numbers are striking. Roughly 70 percent of cancer drugs trace their origins to natural compounds found in plants, microbes, or marine organisms. Antibiotics themselves came from soil fungi and bacteria. Even today, over 30 percent of new drugs still derive from natural sources, despite all our advances in synthetic chemistry. Nature remains the most sophisticated drug discovery engine we have.

At the same time, we’re destroying those systems faster than we can study them. Species are going extinct hundreds to thousands of times faster than natural background rates. Only about 7 percent of known plant species have ever been evaluated for medicinal use, yet more than 20 percent of known medicinal plants are already threatened with extinction. In practical terms, that means we may be losing future therapies before we ever know they exist.

If you want to go deeper into this, I reviewed a paper on how biodiversity underpins human health, medicine, and immune function here. And if you’re curious about the uncomfortable idea that we may be losing important medicines to extinction faster than we can discover them, I explored another paper on this topic here.

This isn’t just about drugs, either. Habitat destruction increases the risk of zoonotic disease spillover, destabilizes ecosystems that buffer pathogens, and even affects our own immune systems by reducing environmental microbial diversity. The COVID pandemic showed us what happens when those boundaries break down. The next one won’t be a surprise if we keep pushing in the same direction.

That’s why the Avatar metaphor works. The real loss isn’t the obvious one. It’s the invisible loss of options, resilience, and future breakthroughs. When an ecosystem collapses, we don’t just lose species. We lose possibilities. Sometimes, we lose cures we never even knew we needed.

A Reality Check for Flu Season

All of this feels especially relevant right now, because we’re in the middle of flu season.

Coming off call, it’s the same pattern every winter. Flu, RSV, upper respiratory infections. None of them unusual on their own, but together they put real strain on hospitals and on people.

A few simple things still matter more than we like to admit. Getting enough sleep. Staying home when you’re sick. Basic hand hygiene. All these things are boring, but effective.

Vaccination helps too. The flu shot isn’t perfect, but it does meaningfully reduce the risk of severe illness and hospitalization, especially during heavy seasons. I reviewed the real-world data and why effectiveness varies year to year here if you want to see the numbers:

Flu Vaccine Effectiveness: How Well Does It Prevent Severe Illness in Adults?

And when people do get sick early, one approach I’ve been interested in is a short-course strategy sometimes called the “vitamin D hammer.” It’s not a replacement for vaccines, and it’s not based on large randomized trials, but there are clinical reports suggesting rapid symptom improvement when high-dose vitamin D is used briefly at the start of illness. I reviewed the evidence, dosing, and limitations here:

The Vitamin D Hammer: A High-Dose Strategy for Beating the Flu Fast

The Long View

The story of penicillin, the resurgence of phage therapy, the lessons from biodiversity, and even the flu season unfolding right now all point to the same idea. The breakthroughs that protect us most don’t come from rushing or extracting every last drop of value as fast as possible. They come from patience, stewardship, and paying attention to systems that took a very long time to evolve. When we respect those systems, whether it’s an ecosystem, an antibiotic, or our own immune response, they tend to hold up remarkably well. When we don’t, the consequences are rarely immediate, but they’re almost always inevitable.